Now that it’s officially autumn here in the UK, my prompt for you this week is to look out for conkers and sweet chestnuts! (By the way, I seem to be getting more subscribers from overseas lately, so my apologies to those of you who are gearing up for spring blooms and warmer days… Thank you for being here regardless, I hope this newsletter is interesting for you even if it’s not seasonally relevant!)

One of the things I love most about my relationship with nature is the childlike sense of wonder and feelings of nostalgia it brings out in me. Last year when I came across a patch of alpine strawberries and popped one in my mouth I was instantly transported back to my grandparents’ garden and eating the sweet, miniature fruits as a child. Conkers stir up a similar nostalgic feeling (though not from popping them in my mouth, PLEASE don’t try and eat them!!). We’ve all got memories of picking up conkers on a crisp autumn day, right?

The first known record of the game of conkers is from the Isle of Wight in 1848 and the game spread across Britain during the course of the next century. Each October, thousands of people still travel to the village of Southwick in Northamptonshire to enter the World Conker Championships, which has been running since 1965. Incidentally, the 2023 Championships happens this weekend… and as far as I know, you still have time to enter!

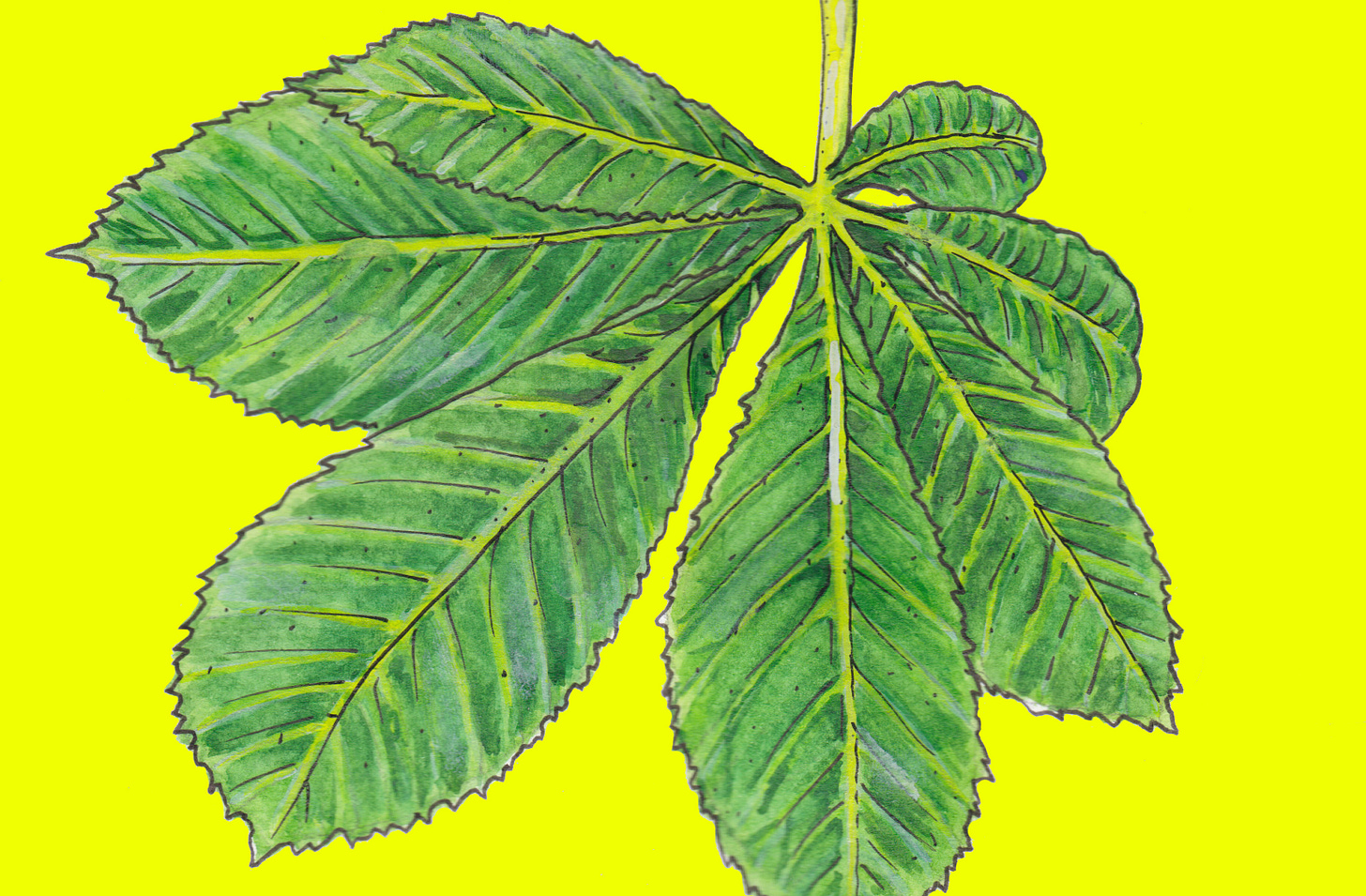

Conkers come from horse chestnut trees, which can be found all over Britain, but are originally native to the Balkan Peninsula and were first introduced to the UK from Turkey in the late 16th century. If you don’t fancy reliving your youth with a game of conkers, you might consider picking some up off the ground to help protect your clothes from moths. As conkers dry out they produce a chemical called triterpenoid saponin which acts as a moth repellent. There are several other uses for conkers too - apparently the Vikings used them to make soap and you can use them to make laundry liquid with a little effort if you gather a couple of handfuls.

If you’re after something edible, it’s the sweet chestnut tree you want - it’s this tree which produces the chestnuts you may recognise from… errr… roasting on an open fire (or more likely from the nets/vacuum packed bags you find in the supermarket at Christmas). Humans have been eating sweet chestnuts since ancient times! You can eat them raw, roast them or freeze/refrigerate them for later use - here are some tips for cooking and preserving.

Sweet chestnuts have an extremely spiky case - yes, even spikier than those pesky conker cases - so if you want to collect some, your best bet is to roll them gently under your (booted) foot until the nuts fall away from their spiky sheath. Here are some more details from Wild Food UK on foraging for sweet chestnuts and here’s a video from Fieldstudy which shows you how to differentiate sweet chestnuts and conkers. Happy foraging!

Important notice: Never eat something unless you’re 100% sure you can identify it correctly. Do your research and make sure it’s safe to eat, and in what quantities. In the UK, we have common law to forage the four Fs (fruit, flowers, fungi and foliage) for personal consumption, but never uproot anything without permission and only take what you need if it’s growing in abundance - leave enough for wildlife to thrive!

If you’d like to learn more about trees and live in London, you might like to attend this Sunday’s Wild Walk at Marvels Wood in Mottingham, hosted by my friends Rosanna and Lucy from Wild South London (a new community group of which I am chairperson). Free tickets are available on Eventbrite.

You may also like….

Connect with your senses

It’s often said that there are five key ways to connect with nature: Contact, Emotion, Beauty, Meaning and Compassion. Today we’re going to focus on Contact, so I’d like to encourage you to tune into your senses. I’m going to share some prompts, but the tasks will really be led by you. Maybe you want to focus on one sense each weekday next week or perha…

Forage & Feast: Nettle Seeds

I bet that, no matter where you live, you won’t be far from a big patch of nettles. You might even eaten nettles before - perhaps you’ve used the young leaves to make nettle soup in spring (or my new favourite cake)… but have you ever eaten the seeds?