“When the Creator painted all the birds’ feathers with their final flourishes of colour, the little brown nightingale was the last in the queue. By then all the paints were used up, except one dab of gold left on the brush – just enough to cover the nightingale’s tongue. Since then, as soon as nightingales return in April, they proudly show off their golden tongues, in a virtuoso performance of colourful song from dawn to dusk.”

(From Telling the Seasons: Stories, Celebrations and Folklore Around the Year by Martin Maudsley)

This Monday evening I went on a nightingale walk at a local nature reserve. I was knackered and moody and fully expecting not to hear a nightingale. I’ve never encountered one before, and all I ever hear about these famous birds is how rare and elusive they are.

It’s true, nightingale numbers are thought to have reduced by more than 90% since the 1960s (Holt et al. 2012), so my expectations for this walk were not high.

However, when we turned up, it soon became clear that our chances were good. The park rangers, Hannah and Tamsin, told the small group of us that had turned up hoping for a performance that they’d heard several nightingales during their rounds earlier that day.

Sure enough, we didn’t have to wait long for the show to begin. An impressive song emerged from the first tree we stopped at. We stood and listened, astounded at the nightingale’s range. Hannah informed us nightingale populations in the reserve are increasing year on year and in 2024, over 30 nightingales were recorded in the reserve, which was created on the site of a former gravel pit.

The next tree we stopped at also treated us with a nightingale performance and, through binoculars, we even caught a glimpse of the performer before he flew off.

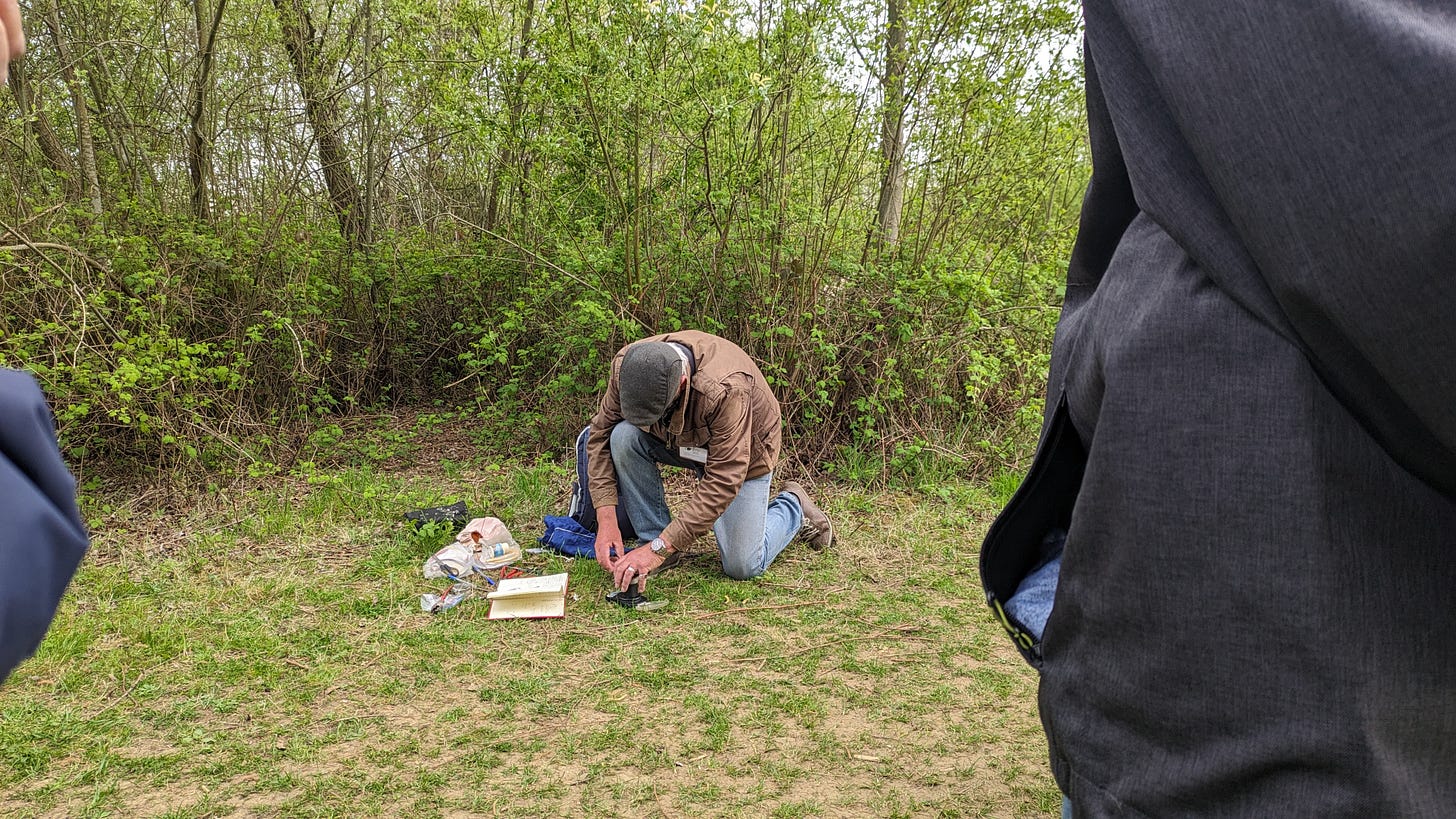

We stopped to talk to BTO volunteer, Alan, an absolute local legend who has been recording nightingales in/around the reserve since 1991. After a quick chat with Hannah, he snuck back into the trees to check his mist net and came out carrying a little cotton bag, out of which - to the sound of our woops and gasps - he carefully pulled a small brown bird.

We watched as Alan checked the nightingale’s ring and noted down its ID number in his notebook. He carefully weighed the bird and lightly blew on its feathers to check its sex (this bird was a female that had previously been recorded on the other side of the park). We all stood there in awe. Not only had we heard three nightingales, but we’d SEEN three - including one up close. And what a beauty she was - not a “boring brown bird” (as we’d commented earlier) at all.

“It doesn’t always go like this,” commented Hannah. We spoke to other attendees who’d been on multiple nightingale walks (in other locations) on which they’d not so much as heard a peep from one. It seems we got very lucky. Not bad for tickets that cost six quid, eh?

So my advice to you this week is: try to see (or hear) that thing you thought you may never see (or hear). Go on the guided walk. Listen to the experts. Take a chance. Try. You never know, you might get lucky.

Nightingale Facts

Nightingales (Luscinia megarhynchos) only spend time in the UK between April and September.New BTO science has discovered Nightingales breeding in the UK spend the winter months in a very small area of West Africa, in and around The Gambia.

The date nightingales arrive back in the UK is becoming earlier, probably due to the climate crisis. Conservationists have warned that the UK nightingale population is in freefall, having declined by 90% between 1967 and 2022.

Only the male nightingale sings and studies show they are able to produce over 1,000 different sounds! You’re most likely to hear a nightingale sing in April and May, as they try to attract a female. Those continuing to sing into June will be desperately trying to entice a mate!

Nightingales migrate back to the same small patch each year. They prefer scrubby areas on the edge of woodland. The rangers and volunteers who showed us the nightingales at our local reserve said they think the buddleia in the park has helped them attract so many nightingales, despite the fact it’s not their normal habitat.

The first ever live radio broadcast of birdsong featured a nightingale singing with the cellist, Beatrice Harrison, in her Surrey garden in May 1924. BUT it was later revealed by the BBC that the bird on the recording was likely not a nightingale at all, and was actually Madame Saberon, a very talented whistler who stepped in for the bird when he seemingly got cold feet! (You can read more about this nightingale fake news via the first link below).

Wonderful. I’m lucky enough to have four or five singing males each spring, walking distance from my house!

I love this, Nightingales are so precious. I do hope they can build in numbers so we don’t lose them completely. A wonderful post in tribute to them 🌱